AUTHOR OF ‘BREATHE’, THE SUNDAY TIMES CRIME BOOK OF THE YEAR 2018

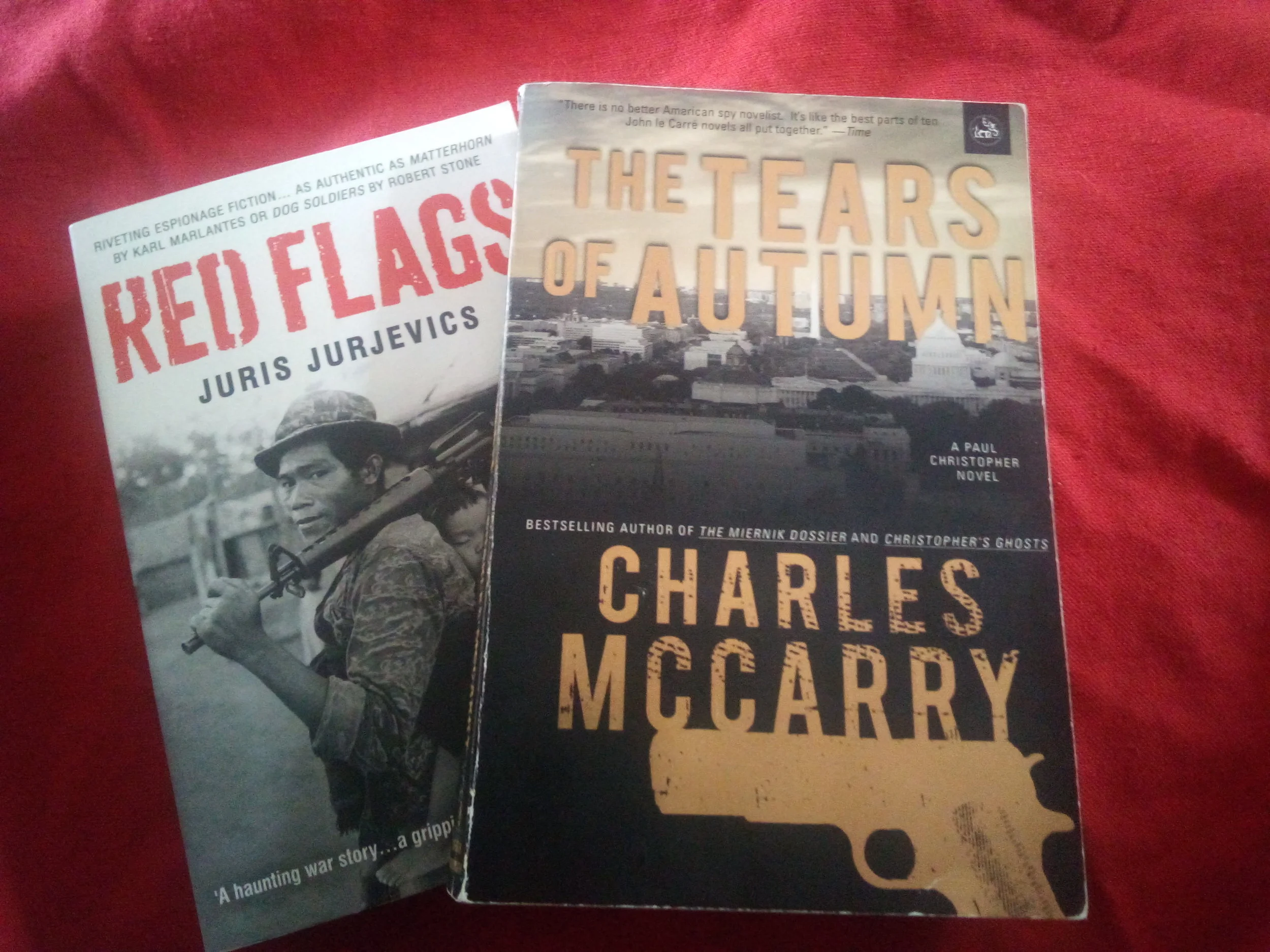

Ten months into the business of being a published author, and one of its greatest pleasures – free books – has yet to pall. I still get a childish thrill when a padded envelope thuds onto the doormat and I tear it open to see what the Proof Fairy has brought…

It isn’t often one gets to read a thriller writer’s every novel, back to back. But last year I volunteered to talk about an old favourite, Gavin Lyall, at an ‘Authors Remembered’ panel at CrimeFest 2019; given the probability that at least one person in the audience would have either a) known Lyall, or b) re-read his books obsessively every year, I thought I’d better brush up. Would that most research were this much fun…

Fifteen years ago I acquired a War Studies PhD. And one of the key takeaways from all the research that went into it was this: wars happen because of the societies they happen in. There’s some elemental clash fundamental to that place and time that means people turn to organised violence to resolve it. And while outsiders may provide the catalyst, may even get involved, they can’t provide the solution – that will lie within the warring society or societies…

Christmas on Skye with a copy of ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ brought pursuit thrillers to mind. For those who don’t know John Buchan’s book, perhaps a third of it is a chase across the moors of south-west Scotland, with hero Richard Hannay enlisting what now seem improbable helpers (a road-mender, a literary innkeeper, a young toff) to keep him out of the clutches of the Black Stone…

One of the great pleasures of being a history buff is mining seams – themes, periods, countries – you love. One of the great handicaps of being a history buff is refusing to mine new ones. I’ve loved Bernard Cornwell’s novels for thirty years, but can’t get into his Arthurian or American civil war fiction – a rejection I can only ascribe to some kind of period prejudice; after all, he’s deploying the same ingredients as in the Sharpe and Uhtred novels, and is certainly applying the same enviable skill…

When I was eight we went on a family holiday to Italy, and as a treat beforehand my parents let me and my brother choose a few books in the old Blackwells paperback bookshop on Broad Street in Oxford. I can’t remember what I got, but I do remember that among my parents’ booty was a clutch of Gavin Lyall thrillers…

If, like me, you've taken a while to get your first book out, you spend a lot of time feeling a bit of a fraud. Failure to deliver makes you wonder if you ever will; mention the book in conversations with new acquaintances and the lack of a publication date can generate a glint of scepticism in their eyes. ('Ah yes, I'm not writing one either.') Only in the last two months has that feeling gradually dissipated…

To be told that your book is 'an outstanding debut... that deserves to win prizes' is invigorating; to have The Sunday Times declare it to (let's hope, here) millions is a shot of adrenaline; to have The Sunday Times also name your novel 'Crime Book of the Month' is leap-tall-buildings-with-a-single-bound stuff…

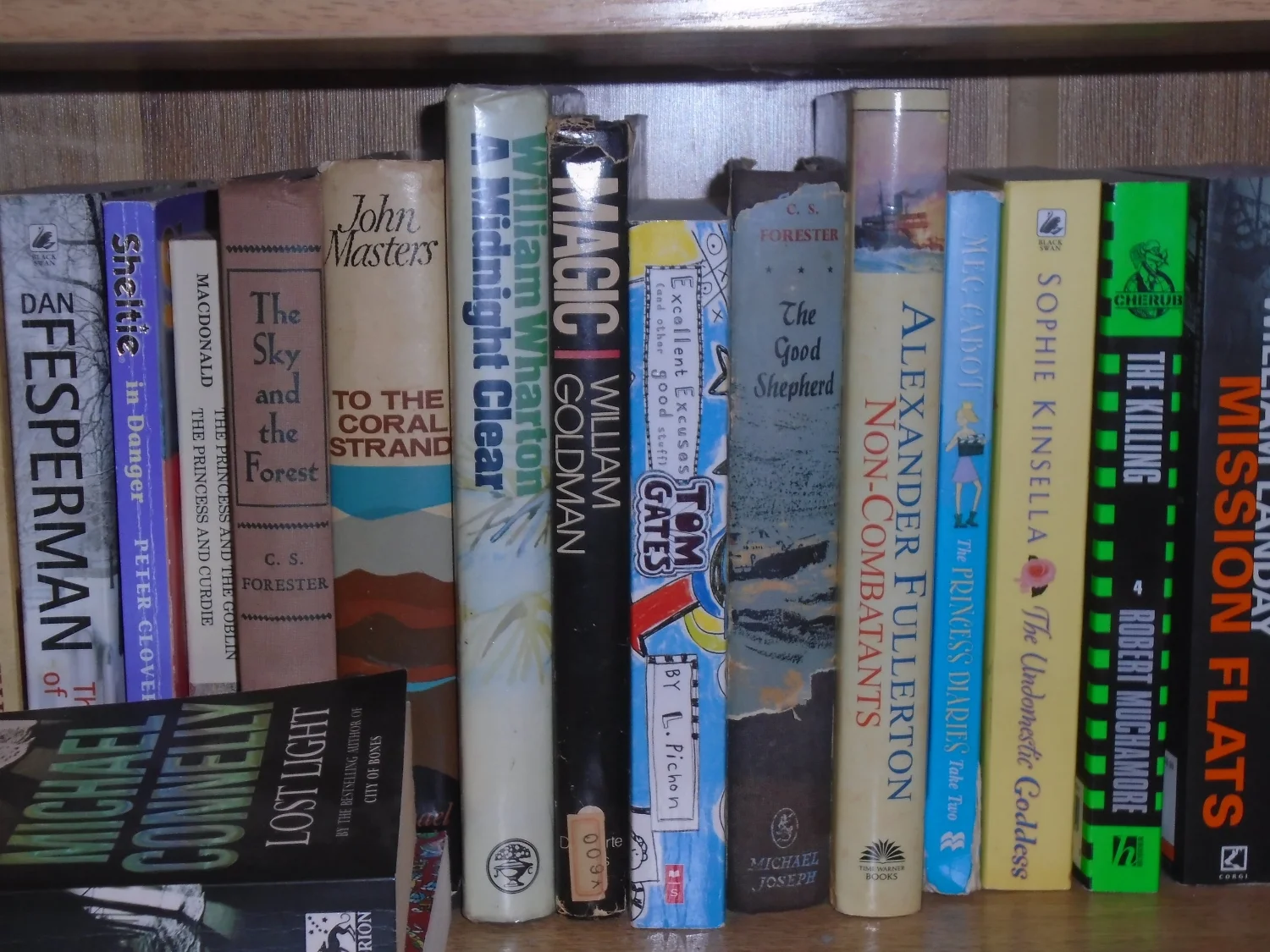

No matter how well I pack, there almost always comes a time on holiday when I find myself turning to someone else’s bookcase. If I’m staying with friends or family, or on home turf, there probably won’t be many surprises; I can generally find something by someone I know. But if I’m abroad…

The path to getting published is a constant education. Things I had no idea of until this year included crime writing festivals (I’m a fan and I’d never heard of such a thing); the particular skill of fiction copy editors, who put my previous lodestar for omniscience, the newspaper sub – now endangered – in the shade; and the importance of bound proofs…

ABOUT ME

I have come to thriller writing late, by way of - in chronological order - intelligence reports, TV scripts, book reviews, newspaper editorials, UN Security Council resolutions, a PhD thesis and political risk analysis. I am not sure any of my previous writing experience really helps with fiction, other than as training - training in how to write for effect, and for the audience. (And anyone who thinks UN Security Council resolutions are dull should be part of the drafting process: achieving the right effect in the right audience takes multiple drafts and a ridiculous amount of verbal dexterity, usually against a very tight deadline.) Perhaps more valuable have been my decades of reading crime and thriller fiction; I know what I think works, and hope to avoid writing what doesn't.

I am inspired by the byways of history - the stuff that people might not have noticed or seen the value of, rather along the lines of Shakespeare's thief Autolycus ('the snapper-up of unconsidered trifles'). The plot for my first thriller, 'Breathe', took shape when I found out that the trigger for the final murder spree of an infamous London serial killer was - indirectly - the city's worst ever smog in December 1952. The smog was extraordinary - five days in which the city was stopped dead by a yellow haze that laced lungs with sulphur and killed thousands. Once I'd discovered that, the combination of this murderer, and the 1952 smog, was just too good to pass up.

The plan is to write thrillers that work with history rather than manipulate it, partly because I was trained that way, by mostly because I love it too much to abuse it.